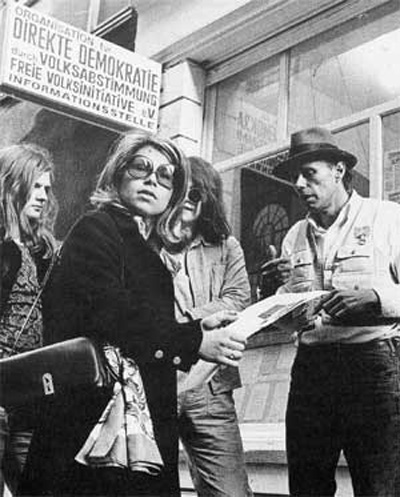

Joseph Beuys - “Organization for Direct Democracy by Referendum” to initiate conversations on a range of topics including politics and art.

Joseph Beuys, Bureau for the Organisation of Direct Democracy, Documenta 5, 1972 © metamute.org

© greenmuseum.org

One of the most well known instances of education as a form of art appears in Joseph Beuys’ practice beginning in the 1970s. While earlier efforts undertaken by the Russian Constructivists, the Bauhaus, and the faculty of Black Mountain College, among others, sought to erode the distinction between art and life through educational vehicles, they did not appropriate pedagogical forms in their artistic production, using them instead as a means to an end. By contrast, Beuys presented scores of educational lectures as performances, documented in a series of photographs and blackboard drawings that register the artists’ actions. Alain Borer has compared these “drawings” to the black monochromes of both Kasimir Malevich and Ad Reinhardt, but makes an important distinction, stating that Beuys’ monochromes form a larger and single “didactic installation” characterized by a continuous temporality, which Beuys described as a “permanent conference.” Thus, these performance-lectures were not temporally bounded in a string of discrete, finite events, but were intended to prompt further discussions carried out by the audience (post-performance) in a situation not unlike Documenta 5 (1972), where Beuys installed an office of the “Organization for Direct Democracy by Referendum” to initiate conversations on a range of topics including politics and art.

These projects exemplify Social Sculpture, a concept and medium the artist devised and later theorized in “I am Searching for Field Character” (1973), which articulates his belief in the creative capacity of every in-dividual to shape society through participation in cultural, political, and economic life. With his proclamation that “EVERY HUMAN BEING IS AN ART-IST,” poised to join others in the construction of “A SOCIAL ORGANISM AS A WORK OF ART,” Beuys reprised the fervor and axiomatic language of manifestos written by avant-garde artists in the early twentieth century. This promulgation expanded what art could be by acknowledging the viewer’s ability to co-create meaning alongside the artist and, consequently, placed the production of art and knowledge within the scope of the viewer just as much as that of the artist.

In practice, however, Beuys did not relinquish control of his productions so easily and generously, alternately maintaining and mocking the authority invested in his position as artist and as pedagogue. The Düsseldorf Academy of Art fired him in 1972 after he opened his course to any student who wished to attend it, a direct violation of the school’s admissions policy. The postcard multiple Demokratie ist lustig / Democracy is Fun (1973) shows Beuys moments after his dismissal wearing an amused look and broad grin on his face, flanked by uniformed policemen who stand as guarantors of a social order in which free and open education is not permitted. Before, during, and after these events, Beuys encouraged a series of protests at the school, and within the year he had teamed up with writer Henrich Böll to co-found the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research in Düsseldorf as an open forum and site for democratic and creative study and expression.

What is striking about these events, like many of the actions Beuys performed, are the paradoxes that underlie them. On the one hand, the artist sought to secure education and equality for all. But on the other, this mission to democratize society hinged upon his persona and insight, authorized by modernist beliefs in the sensitivity and sophistication of the artist and teacher. As such, Beuys simultaneously challenged and reinforced the patriarchal power structure of the academy and the authority of the artist; a benevolent father he might have been, but a father he was nonetheless. Still, despite its many contradictions, Beuys’ practice laid the groundwork for subsequent movements including institutional critique and relational aesthetics, which have, in turn, revived education as art.

The use of dematerialized mediums such as lectures, classes, and discussions may have conditioned a shift from site-specific art making, in which particularized, physical space was a paramount concern, to institutional critique, which expanded the notion of site to include its sociological frames or institutional context. As Miwon Kwon has observed in her essay “One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity,” for artists representative of this shift, it was “the art institution’s techniques and effects as they circumscribe the definition, production, presentation, and dissemination of art that [became] the site of critical intervention.”“5 (read footnote)”:#note5 Thus, for Kwon, works in this genre favour production that is less visual and material in nature both as a means to resist commodification by the art institution, but also to interrogate the relationship between an artwork and its location.

The performative and pedagogical inflection of Beuys’ art anticipated works of institutional critique including Andrea Fraser’s Museum Highlights (1989) and Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992). In the former, Fraser adopts the character of a docent at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and is filmed leading unsuspecting visitors through the museum on tours. What is uncovered by this performance-lecture is the museum as an institution embedded within a skein of social, financial, and political networks. Ultimately undermining the authority of the museum to determine what art is and signifies, the work uses performance and education (in parodic disguise) as a form of art making. As for the latter, Wilson rearranged museum displays at the Maryland Historical Museum in Baltimore to arresting effect by articulating forgotten or untold histories in a process of public re-education. He selected a set of silver goblets and a pair of slave shackles from the museum’s collection storage and presented them together under the title Metalwork, 1723-1880, bringing to light the politics of museological practice and presentation in terms of repressing certain histories. Here, Wilson, like Fraser, pries open the museum’s role in modeling our appreciation and understanding of art as well as of history (or lack thereof) through performative and or pedagogical strategies reminiscent of Beuys.

(...)

From my research into art projects that take educational forms as their medium, I have observed in the CFU and other works shared concerns and characteristics, which include the following:

1. A school structure that operates as a social medium.

2. A dependence on collaborative production.

3. A tendency toward process (versus object) based production.

4. An aleatory or open nature.

5. An ongoing and potentially endless temporality.

6. A free space for learning.

7. A post-hierarchical learning environment where there are no teachers, just co-participants.

8. A preference for exploratory, experimental, and multi-disciplinary approaches to knowledge production.

9. An awareness of the instrumentalization of the academy.

10. A virtual space for the communication and distribution of ideas.

(© Kristina Lee Podesva)